I first came across Andrés Mario Zervigón’s (Cuban) name while researching a

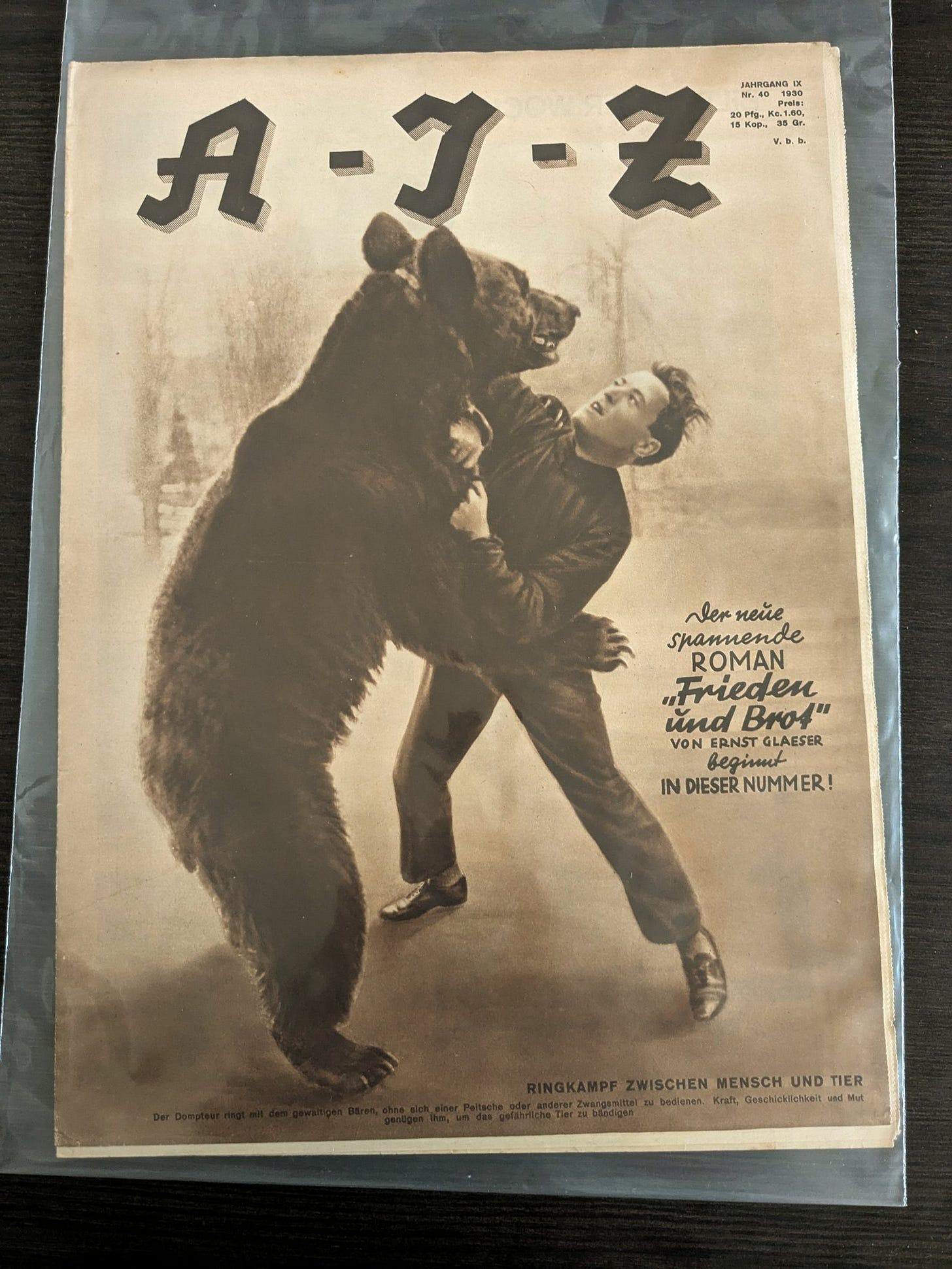

magazine that filled me with awe the first time I looked at it. AIZ, the Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (Workers Illustrated Magazine) is an illustrated, mass circulation German periodical that was published in Berlin during the 1920s and 1930s (in Prague after 1933).

It contains some of the most emotionally charged imagery I’ve ever seen. The best images were created by John Heartfield.

Some 260 full-page photomontages of his appeared in AIZ during the 1930s. Their power, I think, attests to the artist’s ability to leverage not only a personal sense of outrage over injustices that were perpetrated against him in his youth (both his parents abandoned him when he was eight) but also a broader, more universally felt anger, into affecting visual commentary about the atrocities that were being committed in Germany by Hitler and his followers at the time. Many of Heartfield’s best photomontages unveil a timeless ‘truth’: that the rich don’t give a shit about the poor and innocent. Rather, they systematically, savagely, heartlessly exploit and exterminate them for selfish reasons. It’s a Marxist message, told using a Marxist approach to history: retelling, or massaging, existing news coverage (‘evidence’) in order to tell the ‘real’ truth. Only, in Heartfield’s case, with images, instead of words.

Heartfield’s art electrifies. It shocks the viewer with a “bracing” jolt by boldly depicting and unmasking putatively respectable politicians, for example, as the thugs, crooks and murderers they really are. Heartfield’s truth-telling photomontages activate a sort of moral consciousness it seems; they aggravate the conscience. They’re a blatant accusation of crime. A kind of scream for justice. Looking at them triggers a deep muscle memory filled with generations of pent up anger. There’s great emotional power in them. They’re designed to produce a strong reaction, and to jar the viewer into an awareness of the impact that photography is having on them. It’s hard to explain exactly why Heartfield’s work retains its power, partly due no doubt to how brilliantly it exposes hypocrisy and interprets the cultural/political zeitgeist. For sure it's partly due to technique, juxtaposition and stark imagery, but also to how smart Heartfield and his brother Wieland Herzfelde were. They worked together on many projects, including a run of brilliant dust jackets for the successful book publishing company they built together called Malik Verlag. These, along with the AIZ photomontages, are among the first and best works of persuasive ‘pictorial’ art ever designed, intentionally focusing, as they do, on telling emotional stories. As such, they’ve had a huge impact on 20th century visual culture, and on the look of magazines specifically, which is why we’re talking about them.

Andrés Mario Zervigón is professor of the history of photography at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He obtained his PhD from Harvard University in 2000 and concentrates his scholarship “on the interaction between photographs, film, and fine art. His first book, John Heartfield and the Agitated Image: Photography, Persuasion, and the Rise of Avant-Garde Photomontage (University of Chicago Press, 2012), proposes that “photography’s sudden ubiquity in illustrated magazines, postcards, and posters produced an unsettling transformation of visual culture that artists felt compelled to address.”

Zervigón’s work, says the Rutger’s website, “generally focuses upon moments in history when these media [film, photography, fine art] prove inadequate to their presumed task of representing the visual.”

We start our conversation by unpacking this passage, and then move on to a short history of illustrated, mass circulation magazines, (including VU magazine), then to the life of John Heartfield, and finally to AIZ.

Stay tuned for the Backstory, and lots of photos of items from my Heartfield/AIZ collection.

Share this post